In August, I wrote a piece urging us not to buy into the language of ‘shock’ when it is used to describe images of children caught up in war. I was trying to help us fight the dangerous pull of sentimentality, when our human emotions easily cloud our ability to look upon harsh realities.

In August, I wrote a piece urging us not to buy into the language of ‘shock’ when it is used to describe images of children caught up in war. I was trying to help us fight the dangerous pull of sentimentality, when our human emotions easily cloud our ability to look upon harsh realities.

What do we think war looks like, I asked? Of course it looks like children dazed and covered in blood. There is nothing shocking about that image of Omran Daqneesh. He is a child caught up in terrible war. Yes, the image is haunting, awful, gut-wrenching. But it is not shocking. It is depressingly predictable.

My theme was picked up by blogger Tim Dunwoody, writing about the devastation that has occurred in Haiti as a result of Hurricane Matthew. He asked why the images were being described as ‘shocking’, given that Haiti is the poorest nation in the northern hemisphere. He wondered whether those of us who don’t live in abject poverty subconsciously protect ourselves from acknowledging its reality by telling ourselves, in times of disaster, that we are shocked by what we see. He challenges us to be real: “If we are honest with ourselves, surely we know that natural disasters always hit the poor the worst. Do the images from Haiti really shock us?”

My theme was picked up by blogger Tim Dunwoody, writing about the devastation that has occurred in Haiti as a result of Hurricane Matthew. He asked why the images were being described as ‘shocking’, given that Haiti is the poorest nation in the northern hemisphere. He wondered whether those of us who don’t live in abject poverty subconsciously protect ourselves from acknowledging its reality by telling ourselves, in times of disaster, that we are shocked by what we see. He challenges us to be real: “If we are honest with ourselves, surely we know that natural disasters always hit the poor the worst. Do the images from Haiti really shock us?”

I found myself returning to this theme once again as I looked at another of the week’s news images. This time, though, I wondered why we were not using the language of ‘shock’.

The answer is that we were, instead, using the language of ‘cute’. Our laughter at all the cuteness kept us from seeing the possibility of a harsher reality: a child being objectified.

On 10th October, US presidential candidate Donald Trump hosted one of his largest rallies yet. Nearly 10,000 people gathered in Wilkes-Barre Pennsylvania to hear him speak with anger and vitriol about the current state of America and its leaders. Approximately 45 minutes into the speech, he spotted a child dressed up to look just like him. Lots of people had donned costumes for that rally, and the parents of this two-year-old toddler had joined in, dressing him up as a mini-Trump, complete with dark suit, red tie, voting badge and a full head of similarly combed-over hair.

When Donald spotted the child, sitting high on a set of shoulders in the crowd, he invited his security guards to bring him up onto stage. The rapturous crowd loved it.

“What’s your name?” Donald asked.

The child responded with one of the abilities common to all young children learning to talk. He repeated the last word he heard: “Name!” Some of the papers explicitly noted that repetitive pattern in their coverage of the story.

“Are you having a good time tonight?”

“Night!”

“Where’s your daddy, and your mommy? Do you want to go back to them, or do you want to stay with Donald Trump?”

“Trump!”

The roar of approval was deafening. You can hear that “beautiful moment” for yourself here:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GY5OoSlFqAw

It wasn’t just the crowds who loved it. So did the media. ABC News declared that ‘Mini-Trump Steals the Show.” The Toronto Sun said ‘Mini-Trump upstaged Donald Trump’. The Daily Mail charmingly called him the ‘Doppelganger Baby’.

So what’s wrong with any of that, you might ask? It was funny. The kid was cute. Nobody got hurt. The child didn’t even cry. If you look closely, he was smiling. His parents were there the whole time. What is the problem?

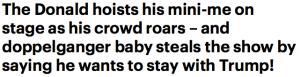

My problem is that our collective response was to laugh indulgently as an angry demagogue used a child for his own political purposes.

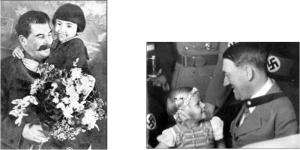

It’s not surprising. In fact, it’s a common strategy amongst demagogues. When they smile at children, they seem more likable. When they get us to laugh with them, we remember ourselves as having had a good time.

And if we’re having a good time, we’re more likely to overlook the ways in which a person is being used to manipulate us. That person (in this case, a small person) has been objectified, used as a pawn in a bigger game.

We have become pawns too. Donald played us all brilliantly: the crowd, the newspaper editors, those of us who looked at that photo and smiled.

Let me be very clear: I’m not particularly criticising him. He was doing what all politicians do: kiss babies. (The Atlantic published a lovely little piece in 2011 on why this “clichéd propaganda” works so effectively.) Donald was also doing what we might expect of a politically ambitious bully under severe threat: he was seizing an opportunity to shift the public mood. Three days previously, most folks around the world had been outraged by the way he had objectified women. He vaporised some of that anger instantly by getting himself photographed being sweet to a cute kid. It’s a brilliant strategy.

I am not in any way reproaching the child’s parents, either. Loads of parents involve their children in political struggles, using their very youth as part of the political point being made. The follow-up interviews (and even the pre-interviews) with Hunter Tirpak’s mother made clear that, as a strong Trump supporter, her aim was to bring positivity to a negative campaign. She is absolutely free to dress her child up as Baby Trump if she wants.

Rather, my critique is focused on us, the public. Why were we so easily entranced? Why did the language of ‘shock’ not appear in any of the papers? Why was this story dripping in froth and fluff, rather than scrutiny?

One answer is that Donald has offered us so many shocking moments during this campaign that we’ve become a bit inured to his antics. And this moment did come just after the meltdown created by his comments about grabbing women by the pussy. It is understandable that, in the face of such blatant objectification, we might miss the more subtle objectification involved in holding up a smiling child for public viewing.

So if you didn’t spot this interpretation, don’t feel bad. Nobody else did either, as far as I can tell. Donald is a very talented showman. He’s better even than Derren Brown.

And if you disagree (perhaps vehemently) with my reading of Donald’s performance, that’s okay too. Debate on the objectification of children would be terrific. It would let us address my earlier question: “What’s wrong with any of this?”

What’s wrong is that objectification is the first step on the journey to exploitation, xenophobia and abuse. When we are astute enough to spot objectification, we stand a better chance of preventing things from getting worse.

One other event occurred in the British media this week that highlights how ‘worse’ it can get. Louis Theroux produced a courageous television documentary exploring how he had failed to spot the sinister depths of his predatory friend, Jimmy Saville. What signs had he overlooked 15 years ago?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j8K9QITg_1Q

The programme made for unsettling viewing – but not because we were watching a man trying to make sense of his own guilt and gullibility. It was unsettling because Theroux was compelling viewers to ask themselves what they too had missed, as they laughed along with Saville, during all the scenes of smiling children. He was trying to help a nation not to get lost in a cloud of guilt and shame, but to have the strength and curiosity to ask: what signs did we miss?

Well, objectification is a pretty good sign.

Well, objectification is a pretty good sign.

The creepy, crazy thing about objectification is that it doesn’t have to feel bad. It can easily feel like entertainment.

Come to think of it, maybe objectification is at its most powerful when it comes wrapped in sentimentality. Who could possibly question laughing at innocent cuteness?