Say the word ‘self-soothing’ in a room of new parents and you are likely to be greeted with facial expressions ranging from exhaustion to frostiness to horror. Be brave enough to talk about it on social media, and you will have created a site of instant conflict. Here’s a recent example from my own Facebook page, with two followers offering very different views on the subject:

Say the word ‘self-soothing’ in a room of new parents and you are likely to be greeted with facial expressions ranging from exhaustion to frostiness to horror. Be brave enough to talk about it on social media, and you will have created a site of instant conflict. Here’s a recent example from my own Facebook page, with two followers offering very different views on the subject:

“Ask yourself how you feel when you are so sad that you cry! You long for comfort and reassurance! If there is no comfort, as an adult you can move about and get something to distract and uplift you! What does a baby have who is distressed and alone? A child who is always left to self-comfort becomes detached and quiet but the emotional resilience is undermined! Reflect!”

“Gosh aren’t women so judgemental about fellow women? I ‘reflected’ long and hard over ten months of no sleep and made the decision to allow my baby to self soothe. I had to, I’m a working mum, not that I have to justify myself to sanctimonious arses. Ladies, make your own decisions and don’t be persuaded away from what you think is right.”

I am grateful to both these respondents. Their comments helped to put me in a place of curiosity. I found myself thinking: ‘What is it about this topic that raises such strong feelings?’ The conclusion I’ve reached is… fear.

The topic of self-soothing hits many of our cultural buttons. These days, we are trying to live exceptionally busy, full lives. Parents are exhausted; babies who cannot fit into a family routine make life harder for the whole household. Parents certainly need sleep if they are going to function at work the next day! Parents want to be good at the job of parenting, but the advice that’s around to help them do that is often conflicting and confusing. They get tired of feeling blamed, judged, and pressured. At the heart of all these emotions is fear – fear that, as parents, maybe we’re not doing a good enough job, fear that we’ll be judged by others as lacking, fear that we won’t be able to juggle ordinary family life.

On the other hand, a growing number of people are fearful on behalf of babies. They are worried about the language that is being used to explain self-soothing. It is worth noting how much contemporary views on self-soothing emphasise the value of independence. Independence is prized in Anglo cultures such as Britain, America, New Zealand, and Australia. When controlled crying is described as a technique that ‘allows a baby to learn to self-sooth’, it sounds like a worthwhile skill to master. It sounds like a way of helping the baby learn how to be independent. That’s exactly what makes some commentators agitated. They are worried that the positive language is misleading parents. The emphasis on independence contrasts sharply with what neuroscience is revealing about babies’ deep dependence on others.

I therefore thought it might be helpful to offer a few insights that speak to that fear and confusion. Here are four points THAT often get lost in the debate:

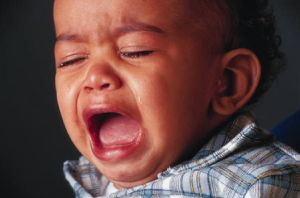

1. There are evolutionary reasons that babies cry.

Babies cry to alert parents that they are in some sort of pain or discomfort. This includes being scared of being alone. Evolutionarily, separation increased the likelihood that the baby would be eaten by a sabre tooth tiger or some other predator. Babies don’t know that the era of predators has passed. Their brains still carry the inherent fear that separation from parents could mean death.

Moreover, it is likely that babies didn’t cry as much in our evolutionary history. Jared Diamond’s 2012 book, The World Until Yesterday, points out that human beings have lived a hunter-gatherer lifestyle for about 90% of our species’ 100,000 years on earth. His observations of the hunter-gatherer societies that remain today show that babies in these societies are in bodily contact with an adult for about 22 hours a day. They are either being carried or are sleeping next to an adult. This results in babies who rarely cry. On average, crying happens for a total of about one minute per hour, and adults pick up crying babies within 10 seconds or less (pg. 183 – 192).

In short, the crying that we now view as normal for babies is actually abnormal, when viewed through an evolutionary lens. The degree to which babies cry may have less to do with their stage of development than with the way that we are all living these days.

2. Prolonged crying raises cortisol levels.

Science is now able to measure the physiological correlates of babies’ behaviour. A range of studies have shown that ‘prolonged’ crying results in increased levels of the stress hormone cortisol, as well as lower levels of growth hormone. (For those looking for a good summary of that research, you might find the webpage for Dr. Sears to be helpful.)

Cortisol is the stress hormone that helps us deal with fear, including fear of being eaten by predators.

How long is ‘prolonged’? One of the notable aspects of the controlled crying /self-soothing debate is that for some parents, this means allowing babies to fuss for a bit, for others it means allowing babies to cry loudly for up to 10 minutes, and for others, it means letting babies cry-it-out until they collapse from exhaustion. I frequently hear stories of husbands and grandmothers who sit in front of the door to help prevent distressed mothers from going in to pick up a crying baby, while the family figures out whether controlled crying will work for them. The reason for the mother’s distress has an evolutionary explanation too: mothers have become physiologically programmed over the past 100,000 years to go and see what the matter is.

So there isn’t a standard definition of ‘prolonged’. It ranges from a few minutes to several hours, and from grizzling to screaming. The definition is one that families reach for themselves. What those families may not know, and can’t therefore take into their consideration, is that the longer a baby cries, the more cortisol is building up in his or her body. The regularity with which that hormone is released will have a big impact on the development of brain pathways.

3. Crying isn’t a behaviour. It’s a signal.

It has become common in our culture to think of crying as ‘just’ a behaviour. That’s not surprising; we value behaviour management these days. Terms like ‘self-management’ and ‘challenging behaviour’ are common in our schools, nurseries, and psychological services. It’s easy to see why parents see themselves as needing to ‘teach’ children how to manage their crying behaviour. Once the crying stops, the problematic behavior appears to have been resolved.

But if we view crying as a signal, rather than as a mere behaviour, we have a new way of approaching the situation. We can get curious about what it’s a signal of. What is the baby trying to tell us? It is ironic that much of the controlled crying advice actually does encourage parents to question, at least to an extent. Parents are reminded to be sure the baby isn’t signaling that he’s hungry or needing changed. These physical needs are acceptable ones.

It is other needs, especially emotional needs for company, which are treated with less indulgence. Loneliness is less legitimate than thirst. If we go back to the evolutionary insight that infants are alarmed by separation, then crying during the night makes sense. You can’t teach someone not to be scared or lonely. You can only support them to find their way out of that fear. The terminology of ‘teaching’ turns out to be as misleading as that of ‘behaviour’.

4. The history of the term ‘self-soothing’ has been lost.

Once an idea gains a name, it becomes a real phenomenon. It can feel like the concept has always existed, so there seems little call to query it.

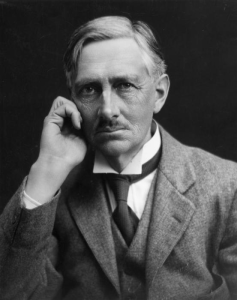

So what is the history of the term ‘self-soothing’? Beliefs that parents should not be responsive to babies go back at least a century, promoted by the early-20th century child expert Truby King. He recommended that babies be fed on a strict 4-hour regime and be held only during feeding, in order to promote emotional independence.

The history of the specific term ‘self-soothing’ goes back only to the 1970s, when it was developed by the eminent researcher, Thomas Anders, based at the University of California, Davis. He coined the term in order to contrast babies who showed a pattern of getting back to sleep on their own (which he termed ‘self-soothing’) with babies who cried upon awakening (which he termed ‘signaling’). Anders’ research wasn’t trying to prescribe what was desirable in babies. He was simply trying to track what happens naturally for babies, and he needed different terms to denote two different patterns. (For those interested in more on this history, see John Hoffman.)

It is fascinating how Western societies have taken a research term into family life, making it a part of their everyday parlance. This irony is heightened by the fact that much scientific evidence, including Anders’ own research, has shown the opposite of what the term implies. Children who are regularly left to cry for long periods have difficulty soothing themselves. They are physiologically less able to cope with negative emotions.

That’s why authors like Tracy Cassels wonder what would have happened had a different term emerged. What if ‘controlled crying’ had come to be known, instead, as ‘systematic ignoring’? Janet Lansbury, too, wonders if we should call it something like ‘helping children to offload’. When faced with such alternative terms, how might our cultural understanding of self-soothing have changed?

So what’s a parent to do? Here’s the answer I’ve reached: strive for curiosity.It is curiosity that gives parents permission to discover who their baby is, confidence about the decisions they are making, compassion toward parents who are struggling to make their family situation work too.

It is curiosity that also lets us see details we might have missed before. For example, when we looked more closely, the modern concept of self-soothing can sound remarkably like Truby King’s ‘old fashioned ideas’. Here’s how Sylvia West summarised King’s views. She speaks from a place of regretful experience, given that her own mother followed his principles stringently:

” ‘Babies,’ King said, ‘are controlling and manipulative from birth, and it is necessary to teach them obedience by making them learn that crying will get them nowhere’. He considered it ‘a dangerous indulgence’ to respond to a baby’s crying: ‘crying is necessary for health, essential exercise for the lungs’. “

How would we describe self-soothing today? Well, here’s one mother’s account:

“Why is it that society seems so set on forcing infants to ‘learn’ to ‘self-soothe’? I hear over and over that it’s so important to not ‘smother’ or mollycoddle your baby so that they ‘learn to self-soothe’, because if you don’t they never will. Don’t pick them up when they’re crying. Leave them to grizzle themselves to sleep in their cot….They need to learn who’s the boss and they need to self-soothe.”

This is not how authors who bring a cautious but positive slant to the topic, such as Janet Lansbury, would describe self-soothing. She offers us a much more nuanced view, which she tries to illustrate in videos such as this one:

A baby’s efforts to self-sooth start long before he resorts to crying.

Once we really understand what the developmental sciences are telling us, we realise with a start that the self-soothing debate isn’t just about our babies. It is also about us, the adults. Who each of us is now was shaped by the way that our parents put us to sleep when we were babies. It can feel mind-blowing to realise everyday decisions matter quite this much.

Our society needs to support parents in being curious. It is only from a place of curiosity that they can come to know themselves and their baby. It is curiosity that drives out fear.

I remember when my daughter was a baby and during the day resisted going to sleep after a feed, I would possibly get 10 minutes before she would start to cry. I was told by the health visitor to just leave her. I did this once and my child got more and more upset , so much so that after 20 minutes she was sobbing uncontrollably when I picked her up. I thought that this wasn’t right – so I got myself a sling and when she wouldn’t go down I put her next to me in the sling and she slept soundly while I got on with the housework. This worked for her and me and I think it is important to consider that every child is different and as a parent/carer you have to do what you think is right for that child and if it cries then perhaps it does need to picked up and held close.

Thanks so much for sharing this story. Stories about how individual families solve this struggle are so important and helpful. I can confirm that leaving babies to cry it out used to be the advice given by many health visiting practices. It is still on some health visiting websites: https://www.healthvisitors.com/hv/5/202 and many mothers share difficult experiences about following the advice of health visitors: https://www.mumsnet.com/Talk/behaviour_development/a1314867-Health-visitor-made-me-cry-it-out.

The neuroscience is leading many health visiting practices to reflect more deeply on this advice, though. Here also is an example of a private practitioner who helps parents negotiate the advice for controlled crying given by health visitors, when it doesn’t work for families: https://live.guru/articles/baby-sleep-advice-for-when-controlled-crying-does-not-work.

My own view is that it is really important not to view parents or health visitors through a critical or blaming perspective, but for all of us to stay very curious about how the neuroscience can help us to better understand babies’ needs and babies’ behaviour. Parents know their baby best, and as a society we need to support them in listening to babies’ needs, not managing their behaviour. Self-soothing is a very contentious issue (which is why I hoped the blog would be helpful to folks).

I would also add: our society needs to have much better understanding of basic infant development. The age of the baby is critically important if a parent is going to try something approaching ‘sleep training’. This point often gets lost in the discussion about controlled crying and crying it out. I see posts on the internet with parents wondering if it is appropriate to try controlled crying with babies only 4 weeks old. Short answer: absolutely not. We all need more curiosity.

Thanks again so much for taking the time to write, so that we can keep extending the conversation for all readers.

Suzanne

I was interested in the video imbedded in your article. As you say, curiosity is key, and a cornerstone to empathy.

I was particularly curious about the context of the video. This baby knew someone was nearby- holding an object which may have partially obscured their face (the video or phone) but there, nonetheless. I suspect the silence of the scene, when usually there may have been talk to the child, the non-engagement of the other, may have interested this infant. It may even have eventually disturbed it. Its attempts at self-soothing may have been arisen partly from this issue.

When a child is left to self-soothe at sleep time, curiosity about how it reads its surroundings will make us think through what we are asking of it. Context will be unique to them, their family and therefore the newest member of that family. The trouble with rules, written by a stranger, are that they underestimate how subtle the dance of parenting is already. Self-soothing is happening from the earliest moments. Of course it is. The child is now external, reliant on others dancing in time with it. So, while those babies are busy learning how to be in the family they find themselves in, we adults can consider what we are using the term for. To get to sleep? To learn to play alone? To feel the fear and do it anyway?

Maura, I love your thoughts. Thank you for sending them. You capture the kinds of questions that I too think are valuable. What is ‘this’ situation (any situation!) like for the baby? That’s the place that curiosity enables us to reach. All cultures have to teach parents how to respond to babies; you have to have some guidance! But thing about cultural guidance that says ‘do this particular thing’ is that it isn’t giving the kind of flexibility that parents really need, in order to get to know their baby.

I am always so intrigued that our focus is on telling parents what to DO, rather than how to BE. We don’t have that focus in other relationships such as, say, adult partnerships such as marriage. We don’t prescribe precise things that should be DONE. Our culture tries to encourage people to find ways to BE together. So there is something special about the prescriptions we often end up providing about relating to babies. Intriguing! I’m glad the video helped you to think more about what self-soothing looks like. It isn’t just crying. It starts long before that. Thanks again for taking the time to write.

Suzanne