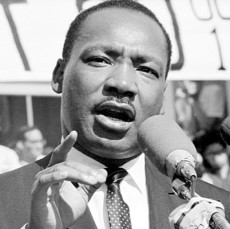

I am writing this blog whilst watching the news that marks the 50th anniversary of Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech. I find myself asking, like many others before me, “What is it about this speech that still speaks to us?”

It was an audacious speech. Audacious in its vision. Yet King’s vision was for something pretty basic: racial justice. That is not an outrageous vision. He wanted black children to be able to use the same water tap as white children. That’s pretty basic. So it wasn’t the content of his dream that was audacious. What was audacious was the context that prevented that dream from materialising automatically. Turning my earlier statement on its head, it was the fact that King needed to make a speech at all that was audacious!

It was an audacious speech. Audacious in its vision. Yet King’s vision was for something pretty basic: racial justice. That is not an outrageous vision. He wanted black children to be able to use the same water tap as white children. That’s pretty basic. So it wasn’t the content of his dream that was audacious. What was audacious was the context that prevented that dream from materialising automatically. Turning my earlier statement on its head, it was the fact that King needed to make a speech at all that was audacious!

And how did he convey the power of his vision to his listeners? “I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will be judged not by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.” King had a dream for his own children, and for all the children of his country.

That is not unlike the process in which Scotland in now engaged. We are actively dreaming for our children, through initiatives such as the Early Years Collaborative. In an earlier blog I celebrated this initiative, launched in 2012, to lift Scotland’s health record from its place near the bottom of Europe. Every single one of the 32 local authorities in Scotland is now signed up to this initiative. The Early Years Collaborative stands a real chance of achieving what campaigners like Mary Lily Walker had been trying to do more than 100 years ago in Scotland: meet the emotional and physiological needs of our kids.

That is not unlike the process in which Scotland in now engaged. We are actively dreaming for our children, through initiatives such as the Early Years Collaborative. In an earlier blog I celebrated this initiative, launched in 2012, to lift Scotland’s health record from its place near the bottom of Europe. Every single one of the 32 local authorities in Scotland is now signed up to this initiative. The Early Years Collaborative stands a real chance of achieving what campaigners like Mary Lily Walker had been trying to do more than 100 years ago in Scotland: meet the emotional and physiological needs of our kids.

How is the Scottish Government conveying its dream? With this straightforward statement: We want Scotland to be the best place in the world to grow up. Everyone who attends a Collaborative meeting is asked to sign up to this vision. That statement now appears in all relevant Government documents. What a wonderfully audacious dream.

I want this dream. I want Scotland to be a place where our children are happy and healthy and confident and know social equality, just as King wanted the children of America to know racial justice. How do we achieve that? What do we need to do so that in 50 years time there is some chance that people will be quoting at least a few lines from some of the speeches being made this year in hundreds of settings across Scotland?

My answer: We need to offer hope. That is why King’s speech worked. He offered hope. Hope that burned and stung and clawed at your heart. King’s hope spoke to people’s pain. That is why his speech worked. That is why 200,000 people found their way to Washington DC that day, in an era without websites or texts or twitter. King’s dream spoke to their personal pain.

Hope is not hope if it does not speak to pain, to frustration, to disillusionment, to fear. They go together, hope and fear. Each needs the other. Hope is the only path out of fear and doubt and worry. I find myself recalling the comments of one of the women who attended a presentation I gave last week in Musselburgh, to East Lothian Council’s network on Support from the Start. She said that the key message she had taken away from the presentation was not about the scientific data but about the power of hope.

Hope is not hope if it does not speak to pain, to frustration, to disillusionment, to fear. They go together, hope and fear. Each needs the other. Hope is the only path out of fear and doubt and worry. I find myself recalling the comments of one of the women who attended a presentation I gave last week in Musselburgh, to East Lothian Council’s network on Support from the Start. She said that the key message she had taken away from the presentation was not about the scientific data but about the power of hope.

Simon Sinek offers an interesting take on King’s speech, summarized inhis 2012 Ted Talk on leadership (embedded below). He says that King’s speech worked because he said “I have a dream.” He did not say “I have a plan.” This is a compelling observation. Its irony actually makes me laugh, which was of course Sinek’s intention. A Movement does not succeed by offering people a plan. If you want a Movement, you need a dream.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wMLSrqYk0UE&w=420&h=315]So I want to say something risky. Remember that I fervently share the dream of Scotland being a fabulous place to grow up. I left a secure job to help further the Early Years Movement in Scotland and beyond.

My risky statement is: I do not think we will achieve our dream. Unless…we offer more hope. We professionals and policymakers are doing something more comfortable for us: we are offering plans. We are doing exactly what Sinek says we should not do if we want to be effective. Our professional networks, full of people who passionately want to make a difference to Scotland’s children, too often take the fascinating neuroscientific insights and the gripping health data, and we reduce them to a plan. And then we tell parents to follow that plan.

We tell them to breastfeed, to read to their children, to monitor screen time, to turn the buggy so that it faces them, to check the content of shampoos, to leave their babies to cry, to give the kids more exercise, to spend more quality time with them. We tell parents what to do. We give them a plan. And when they don’t follow our plan, we imply with our language and our tone that they are inadequate parents. That only irritates them. They feel bossed about and nannied and irritated and resistant.

We tell them to breastfeed, to read to their children, to monitor screen time, to turn the buggy so that it faces them, to check the content of shampoos, to leave their babies to cry, to give the kids more exercise, to spend more quality time with them. We tell parents what to do. We give them a plan. And when they don’t follow our plan, we imply with our language and our tone that they are inadequate parents. That only irritates them. They feel bossed about and nannied and irritated and resistant.

I know all those behaviours are valuable! I know the data tell us that children thrive on these things! But simply telling parents what to do does not help them to parent joyfully and confidently. It doesn’t nurture self-assurance and curiosity and reciprocity. Rolling out our vision by framing it as plans ultimately leads us to undermine our own aim.

What we could do instead is to inspire hope. Our responsibility as professionals could be to walk beside our fellow parents — because most professionals are parents too! – and nurture hope. Our role could be to help other parents to believe that they really can be the great parent that they [too] want to be.

To do this, we will need to take down some of our professional barriers. When did the division of ‘them’ and ‘us’ grow into such definite categories anyway? I have had professionals tell me that, as parents, they do not do in their own lives what the policies require they advise their ‘clients’ to do. If we can get more humanity into our professional practices, we will naturally be boosting confidence. Human brains interpret kind acts of humanity as a vote of confidence in one’s own capabilities. This will be scary though. We will need to embrace less power for ourselves and more trust in our clients.

A focus on common humanity will spread hope because it will enable professionals to listen to parents’ pain – to their frustrations and challenges and doubts. We have to be willing to listen to the squeamishness they feel about breastfeeding, to the struggles they have with monitoring screentime, to the pressures they have on their own time. We have to help parents figure out how to solve those struggles in their own lives. We have to stop talking and start listening!

There is no other choice, because if we really do want Scotland to be the best place in the world to grow up, that cannot be achieved without parents joining this Movement. We need them more than they need us.

So here is my dream for Scotland’s children: that they feel not just loved but valued, that they receive massive amounts of reassurance and encouragement, and that they have much more laughter and silliness and creativity and affection in their young lives. Such early years experiences are crucial to other policy aims we have decided on as a country: secure attachment, school readiness, social skills, mental health, confident learning.

But it sounds outrageous to even suggest some of this. Laughter just does not sound serious enough! The data showing that laughter reduces heart attacks and colds and marriage breakdowns gets pushed aside. We have a fantastic government funded ‘Play Talk Read Bus’. This means we really do get the importance of play, as a society. But we get it because we link play to reading. Reading seems serious and worthwhile. If we called it the ‘Play Talk Laughter Bus’, we would probably be less willing to allocate our taxes to fund it.

I am not talking rocket science. People say to me all the time that the science confirms what they already knew in their heart of hearts. What makes life worth living is laughter and fun and hanging out with people whom you trust enough to relax with. Scotland can never be the best place in the world to grow up unless we explicitly aim to give our children laughter and fun and relaxation and trust. To do that, we need to give those things to ourselves too. We cannot give our children what we do not give ourselves.

I am not talking rocket science. People say to me all the time that the science confirms what they already knew in their heart of hearts. What makes life worth living is laughter and fun and hanging out with people whom you trust enough to relax with. Scotland can never be the best place in the world to grow up unless we explicitly aim to give our children laughter and fun and relaxation and trust. To do that, we need to give those things to ourselves too. We cannot give our children what we do not give ourselves.

So in the week we celebrate Martin Luther King’s vision of a society based on racial justice, I want to suggest that we change the way we approach our early years vision. Let’s talk more about hope and pain and listening and giggling. Let’s create policies that promote laughter. I am not the only one who thinks this. Mum Alicia speaks for many parents when she suggests in her 2010 blog post that “it is more important for 4-year-olds to know how to be silly than it is for them to know how to read”.

Sound too audacious? “Suzanne, you want policies on promoting laughter?? Are you serious?” Well, Martin Luther King needed to make an audacious speech because there were lots of people in a civilized country who did not believe in something as basic as a policy that allowed children to use the same toilet, irrespective of what colour they were. My dream is for something as basic as policies that make sure our children have enough laughter.

Sound too audacious? “Suzanne, you want policies on promoting laughter?? Are you serious?” Well, Martin Luther King needed to make an audacious speech because there were lots of people in a civilized country who did not believe in something as basic as a policy that allowed children to use the same toilet, irrespective of what colour they were. My dream is for something as basic as policies that make sure our children have enough laughter.

Thank you Suzanne for saying what many of us parents think and feel. The links were inspiring too.