In November, my team will host a public lecture entitled ‘How dementia helps us to understand our common humanity’. The speaker, Dr Maggie Ellis, a specialist in dementia care, chose that title because she wanted to bring hope to a topic that is inherently scary.

In November, my team will host a public lecture entitled ‘How dementia helps us to understand our common humanity’. The speaker, Dr Maggie Ellis, a specialist in dementia care, chose that title because she wanted to bring hope to a topic that is inherently scary.

Dementia is frightening because any of us could face it. We are reminded yet again of that possibility by this week’s media story breaking the news that guitarist Malcolm Young has had to withdraw from the legendary rock band AC/DC because he has been diagnosed with the condition. It prompts the facetious query: if even rock stars aren’t safe, what hope do the rest of us have? The reminder that we are all human, all equally vulnerable to an illness for which there is as yet no cure, is indeed scary. The estimates are that by 2015, 7% of the aging population in the UK will be coping with this illness. That’s 1 in every 14 people over the age of 65.

Its somehow comforting expressing the figures in that way: “7% of the population.…” The phrase ‘the population’ sounds safe. It seems we are talking about other people. It doesn’t sound too personal. We have distance from our anxiety. If it is ‘other people’ to which dementia is likely to happen, then it feels less individually threatening. Most of us would rather avoid thinking too much about the likelihood of receiving a dementia diagnosis, thank you very much.

Ironically, that is precisely what I am trying to prevent in this blog. I don’t want us to avoid those negative feelings. I want us to find ways, as individuals and as a society, to turn and face our fear of dementia. We need to do that because, at the moment, our unexamined fear is leading us to misunderstand the illness and those suffering from it. As dementia reaches advanced stages, too many people struggling to live with it end up lonely, anxious and isolated — even though this is the last thing that professional carers or loved ones intend. It does not have to be this bad.

It is uncomfortable to even contemplate that, as a society, we could be ‘doing’ this to elderly people. Yet researchers Helen Sweeting and Mary Gilhooly have described the latter stages of dementia as a kind of ‘social death’, because it is so easy for people with dementia to end up excluded from participating in any social world. Tom Kitwood, the trail blazing campaigner, famously said that the really disabling impact of dementia is due not to the illness itself, but to the reaction that other people have. If we can find the courage to be curious about our own anxiety, we have a chance of recognizing these unintended consequences. We stand a chance of making the lives of people with advanced dementia a whole lot better.

In her lecture on the 10th of November 2014 (taking place at the University of St Andrews), Dr. Maggie Ellis will explore the scientific research revealing that dementia does NOT destroy a person’s capacity to stay emotionally connected to other people. That discovery is surprising. Dementia steals so many things – independence, memory, language, emotional self-regulation, even the ability to move one’s own body – that it can easily seem to obliterate personhood itself.

Dementia does not do that. That will be the central point of Dr. Ellis’ lecture. Psychological studies of dementia are teaching us that the capacity to stay emotionally connected may be one of the last capacities to leave us. Even people with extremely advanced dementia can still be reached. In order for that to become apparent, though, carers will need to change the way they typically engage.

For the past 15 years, Dr Ellis has been working with an approach called ‘Adaptive Interaction’ or ‘Intensive Interaction’. It teaches professional staff and family members to closely match the gestures, movements, rhythms and sounds of a person with dementia – even when those actions seem meaningless, random or embarrassing. The idea that imitative attunement should be effective, or even appropriate, can seem initially disconcerting. That’s why I maintain that we need to bring curiosity to our fear. Maggie Ellis is encouraging us to behave in ways that are not normal or encouraged in most Western cultures.

For the past 15 years, Dr Ellis has been working with an approach called ‘Adaptive Interaction’ or ‘Intensive Interaction’. It teaches professional staff and family members to closely match the gestures, movements, rhythms and sounds of a person with dementia – even when those actions seem meaningless, random or embarrassing. The idea that imitative attunement should be effective, or even appropriate, can seem initially disconcerting. That’s why I maintain that we need to bring curiosity to our fear. Maggie Ellis is encouraging us to behave in ways that are not normal or encouraged in most Western cultures.

Yet the findings being obtained by Maggie Ellis, along with her colleague Professor Arlene Astell, are transformative. They reveal that simply by matching the behaviours of another person, emotional connection emerges. It sounds almost too good to be true. Expect it isn’t. Their findings back up similar claims from groups like Dementia Positive and Hearts & Minds, about the astounding impacts of music, poetry and laughter.

Maggie tells stories of care home residents who have ended up isolated in their bedrooms because staff worried that their ‘constant loud moaning’ was distressing to other residents. Adaptive Interaction demonstrates that such moaning is not random or meaningless. It is meaningful. It can serve as the perfect basis for communicative exchanges. Their research team has gathered a mass of data showing that when carers respond to these behaviours, rather than ignore them (because they are confusing or embarrassing), then emotional connection blossoms. It is not unusual to hear staff who are trained in this method of interaction saying they found it “absolutely astounding.”

Maggie tells stories of care home residents who have ended up isolated in their bedrooms because staff worried that their ‘constant loud moaning’ was distressing to other residents. Adaptive Interaction demonstrates that such moaning is not random or meaningless. It is meaningful. It can serve as the perfect basis for communicative exchanges. Their research team has gathered a mass of data showing that when carers respond to these behaviours, rather than ignore them (because they are confusing or embarrassing), then emotional connection blossoms. It is not unusual to hear staff who are trained in this method of interaction saying they found it “absolutely astounding.”

I agree. The outcomes yielded by Adaptive Interaction do feel astounding. To suddenly find yourself connecting with a person, even fleetingly — complete with turn-taking, smiles and mutual gaze — feels astounding if you have experienced that person as entirely vacant in the preceding weeks and months.

Yet, it only feels astounding. Human beings are born connected. Those who follow my blogs and wider work will have heard me make that statement countless numbers of times. When we truly ‘get’ what that single sentence means, then the outcomes yielded by Adaptive Interaction, along with the music, poetry and laughter (as you can see below), make sense. Research with dementia patients is teaching us the same thing that research with infants has taught us: human beings are innately communicative. Human brains are biologically programmed to search for meaning in other people’s behaviour. Dementia ‘patients’ have not lost that biological programming. Whatever other deterioration their brain is undergoing, it continues to search for responses from the people around them.

[youtube=https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tuj8MMDBJrA]

Therein lies Maggie Ellis’ message of hope. Dementia does not rob people of personhood. It wreaks other tremendously sad forms of loss, but it does not dissolve a person’s core humanity. One reason that so many of us think it does is because Western adults tend to equate ‘communication’ with ‘language’. In contrast, the advanced stages of dementia take us back to a different form of communication: the non-verbal one with which we were all born.

And herein lies a problem: letting go of our adult attachment to language is deeply uncomfortable. When Maggie Ellis talks about her work, she is frequently greeted with a response like this: “But are you saying we should treat elderly people like babies? Are you saying we should babble back at them and make silly faces with them? That’s not dignified.”

And herein lies a problem: letting go of our adult attachment to language is deeply uncomfortable. When Maggie Ellis talks about her work, she is frequently greeted with a response like this: “But are you saying we should treat elderly people like babies? Are you saying we should babble back at them and make silly faces with them? That’s not dignified.”

We want to treat other people with respect. Of course we do. Yet, once an elderly person loses the ability to talk, we aren’t always sure how to offer that. We become uncomfortable with the idea of shifting to a new style of communication, reluctant to ‘give up’ on the abilities that person once possessed, afraid that the person we once knew would have felt embarrassed had they ever imagined themselves in this situation. We project onto another person what we imagine we might feel ourselves. We unconsciously get ourselves tied up in knots about how to offer someone something as basic as respect and kindness.

One of the inviting aspects of Maggie Ellis’ work is that it redefines respect. She argues that it is responsiveness itself that is respectful, not its form. In fact, she goes further. She contends that to refrain from responding is disrespectful. It is also isolating. When we fail to treat the gestures and utterances of people with dementia as communicative, we are effectively abandoning them. We leave them lonely, anxious, disconnected. She sees this as disrespectful, unkind and harmful. She fully accepts that the disrespect is not intended on the part of staff members or loving family members. It comes from a complete lack of understanding that behaviours like screaming or jerky head movements could be in any way communicative. That’s why she’s on a mission to educate the public about the communicative capacities that lie at the core of our humanity.

What I love about Maggie Ellis’ vision is that it overlaps so unexpectedly with that of infancy researchers. Both scientific communities are trying to help the public to understand the profundity that lies at the centre of the human attachment system.

Indeed, attachment theory is now driving some cutting-edge avenues of dementia research. Professor Linda Clare leads a team based at Bangor University in Wales, who are beginning to map behavioural symptoms of dementia, such as pacing, rocking, calling and crying, onto the very same attachment behaviours that have been studied by researchers focused on childhood. Those findings show that individuals exhibiting a secure attachment style are more likely to show positive emotions (e.g. joy, interest) and less likely to show distressed emotions (e.g. anxiety, fear, hostility). This means that behaviours currently viewed as ‘symptoms’ of dementia can actually be seen as attempts to self-regulate emotion. Yet most staff working in care homes will never have heard of attachment theory, let alone received any training in it, because attachment is so often associated exclusively with childhood. One we really ‘get’ that attachment is life-long, that it is simply part of the human condition, then we have a whole new way of making of sense of behaviours that are confusing and frustrating for so many care staff and family members.

Indeed, attachment theory is now driving some cutting-edge avenues of dementia research. Professor Linda Clare leads a team based at Bangor University in Wales, who are beginning to map behavioural symptoms of dementia, such as pacing, rocking, calling and crying, onto the very same attachment behaviours that have been studied by researchers focused on childhood. Those findings show that individuals exhibiting a secure attachment style are more likely to show positive emotions (e.g. joy, interest) and less likely to show distressed emotions (e.g. anxiety, fear, hostility). This means that behaviours currently viewed as ‘symptoms’ of dementia can actually be seen as attempts to self-regulate emotion. Yet most staff working in care homes will never have heard of attachment theory, let alone received any training in it, because attachment is so often associated exclusively with childhood. One we really ‘get’ that attachment is life-long, that it is simply part of the human condition, then we have a whole new way of making of sense of behaviours that are confusing and frustrating for so many care staff and family members.

We can also make better sense of research findings like the one reported in this week’s media (sometimes printed right underneath the story of Malcolm Young). A new study published in the journal Neurology, conducted by researchers in Sweden, has found that women who frequently experience intense emotions like anxiety, jealousy and distress in middle age are more likely to develop dementia in later life. The women who scored the highest on tests for neuroticism had double the risk of developing dementia, as compared to those with the lowest scores. The reports described these emotional patterns as ‘personality characteristics’. They could just as legitimately be described as ‘attachment patterns’, since the aim of the human attachment system is to craft one’s physiological ability to regulate emotions.

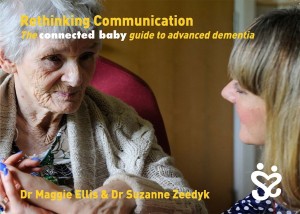

That is why Dr Ellis’ lecture on the 10th November will also serve as the launch for the new book that she and I have co-authored. Entitled Rethinking Communication, it is the latest addition to our growing series of ‘connected baby guides’. The goal of the short book is to unpack the kind of themes I have been exploring in this blog. Our hope is that the book will be of interest to a wide range of individuals and organisations, including care home staff, NHS staff, charities easing the impacts of dementia, and family members seeking ways to stay in contact with their loved ones. It explains why Adaptive Interaction works and gives readers a clear sense of how they could try using it themselves.

That is why Dr Ellis’ lecture on the 10th November will also serve as the launch for the new book that she and I have co-authored. Entitled Rethinking Communication, it is the latest addition to our growing series of ‘connected baby guides’. The goal of the short book is to unpack the kind of themes I have been exploring in this blog. Our hope is that the book will be of interest to a wide range of individuals and organisations, including care home staff, NHS staff, charities easing the impacts of dementia, and family members seeking ways to stay in contact with their loved ones. It explains why Adaptive Interaction works and gives readers a clear sense of how they could try using it themselves.

Our predominant emotion as we wrote the book was one of excitement. The opportunity to put attachment theory into such practical use was irresistibly inviting. It is only as we draw near the release date that I have realised quite how radical the book is. Just last week, someone wrote to me:

“Is the world ready for this, Suzanne? What with political correctness being what it is, and the concept of dignity in care being so fundamental. Will people think that you are arguing we should treat dementia patients like babies? I know that people who understand brain development will probably get the idea, but do you think they will feel confident enough to take it back to their peers?”

I found myself thinking: “Goodness. There it is already. The very same worries that Maggie Ellis and others have been tackling for 15 years and more.”

Come the launch on the 10th of November, we will see if our new publication can help to make a bit more difference. Maybe what society has needed all along is the linking up of neuroscience, infant science and dementia science. This brings a whole new impetus to governmental prevention initiatives, such as Scotland’s Early Years Collaborative.

Come the launch on the 10th of November, we will see if our new publication can help to make a bit more difference. Maybe what society has needed all along is the linking up of neuroscience, infant science and dementia science. This brings a whole new impetus to governmental prevention initiatives, such as Scotland’s Early Years Collaborative.

Those of you follow my blog will be amongst those who, as my correspondent above put it, “get the idea”. People with dementia need your help. We need you to feel confident enough to take this idea back to your peers – and to your family and colleagues and local journalists.

Dr. Maggie Ellis’ public lecture takes place on Monday, 10 November, 7 – 9 pm, at the University of St Andrews. Tickets are free, albeit limited, and can be booked through Eventbrite.

The book ‘Rethinking Communication: The connected baby guide to advanced dementia’ will retail at £5.00 per copy. Advance orders can be requested from karen@suzannezeedyk.com or by phoning: +44 (0)845-9975-3694.

I find this all very interesting. I worked in early education for many years…. I am now retired and distance caring for two elderly aunts. They live together, independently. All their lives they cared for their elder sister with special needs. Sadly, she died 2 years ago. Since then, there has been a marked deterioration on both the remaining aunts. One more than the other. Concentration, forgetfulness, appearance, motivation, tiredness, self-confidence and muddled communicative ability. There has been no diagnosis of dementia, because they are both plodding along with the help of both myself and my sister and each other, and to be honest, I’m not sure they have reached the point where we need any diagnosis, however, I do think they are heading towards this. I now intend to investigate and read more about the subject of Dementia.

What fantastic and essential information.

Head on approaches like this will help to confront the “fear” of dementia which leaves so many people with dementia isolated and their visitors feeling helpless.

It would be meaningless going to another country and continue to talk English. Adaptive Iteration is not treating people with dementia as babies. Common behaviors and copying behaviors can be used to create new lines of communication. It just happens to be so deeply rooted in us as humans that it comes before the acquisition of language, that’s where the association with babies ends.