We are conflicted about nappy changing these days. As a society, it makes us uncomfortable. It is distasteful, involving dirty, smelly bodily substances. It is anxiety provoking, requiring the exposure of babies’ genitals. It is inconvenient, necessitating a pause in the midst of whatever other activity a parent has underway. And it frequently emotional, with babies refusing to lie still or staring intently into their caretaker’s face.

For all these reasons, nappy changing is something we don’t usually talk about in polite circles. It may be a necessity of life with a baby, but it’s not exactly a subject for the dinner table, is it? It might therefore seem too inconsequential a topic for a whole article, especially when you consider that other pieces in this blog series have focused on ‘serious’ subjects, like terrorism and abuse and brain development.

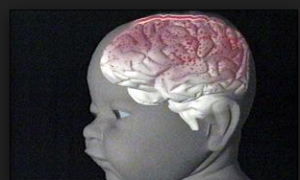

Yet, to my mind, that is exactly the reason for writing a piece on nappy changing. Babies’ brains grow more rapidly during the period of life during which they need their nappies changed than will ever be the case again. Approximately 1000 synaptic connections are formed every second during this period. Astounding. And it is the emotional experiences that babies have over and over again that build the most robust neural pathways. Nappy changing is undoubtedly an activity that babies encounter repeatedly. Indeed, over just the first six months, there are approximately 10 changes per day, each lasting, say, 5 minutes. That’s 9000 minutes or 540,000 seconds, and thus half a billion synapses.

Yet, to my mind, that is exactly the reason for writing a piece on nappy changing. Babies’ brains grow more rapidly during the period of life during which they need their nappies changed than will ever be the case again. Approximately 1000 synaptic connections are formed every second during this period. Astounding. And it is the emotional experiences that babies have over and over again that build the most robust neural pathways. Nappy changing is undoubtedly an activity that babies encounter repeatedly. Indeed, over just the first six months, there are approximately 10 changes per day, each lasting, say, 5 minutes. That’s 9000 minutes or 540,000 seconds, and thus half a billion synapses.

So nappy changing isn’t quite as inconsequential as we might at first have thought. It has an impact on babies’ brain development. More specifically, the emotional experiences that caretakers give babies whilst changing their nappies are being built into babies’ brains.

I thought, therefore, that it would be interesting to reflect on the ways in which modern society encourages us to approach the task of nappy changing. This is an appropriate moment for such reflection, given that Real Nappy Week is taking place this very week in London. Most people won’t have any idea there is a group of committed individuals who want to celebrate the benefits of real cloth nappies. This article is my way of supporting their efforts.

So what are some of the big messages we get about nappy changing in today’s society?

One message is that nappies are disgustingly funny. Take, for example, the videos that regularly travel the web that show fathers wretching whilst changing nappies. In August 2015, a tattooed, uniformed father gained international attention when the video of him vomiting as he soldiered on with nappy changing went viral, featuring eventually on television and in newspapers.

One message is that nappies are disgustingly funny. Take, for example, the videos that regularly travel the web that show fathers wretching whilst changing nappies. In August 2015, a tattooed, uniformed father gained international attention when the video of him vomiting as he soldiered on with nappy changing went viral, featuring eventually on television and in newspapers.

Why is it always Dads? I know that we regard ourselves as having ‘moved on’ as a society, because once upon a time fathers never changed nappies at all. But this humiliating form of humour says something darker about the way we frame modern masculinity. We are either laughing at dads’ incompetence – or turning them into heroes for coping with something ordinary. Indeed, if you want a gag gift for new fathers, you can buy a ‘doodie apron’, which comes complete with nose peg, face mask and gloves, all designed to help a father keep the disgusting productions of his baby’s body at bay.

I know it’s supposed to be funny. And I know I sound like I need to get a life if I’m not laughing at the innocent joke. But I find myself wondering about the baby’s experience. Is the baby scared when confronted with Dad clad in a face mask? Does the baby feel ashamed when Dad looks disgusted in reaction to the substances that her body produces? Does the baby feel embarrassed when parents start laughing whilst filming ‘poo faces’ to send to Pampers as part of an advertising campaign?

Here’s my point: we feel okay about all this laughter because we think it’s only about the adults. We don’t think it matters to the babies. We wouldn’t laugh at older people with dementia who are pooing, because we would think that was disrespectful. But when it comes to babies, we think they don’t notice. That why the joking seems innocent and can’t do harm to anybody.

Except it’s not true. Babies are born with a connected brain. That means they are already aware of and attuned to and reading other people’s emotions, facial expressions and behaviour. Babies learn about themselves by the way we treat them. This includes the way we treat them during activities as ‘inconsequential’ as nappy changing. If we react often enough to babies’ bodies with disgust, then they start to see themselves as disgusting. It is ominously fascinating to realise that we can build a sense of shame into our child’s brain by the way we treat them during nappy changing. As parent, we can do that without ever realizing or intending to. And modern society makes it more, not less, likely that we will do just that.

What’s another message that we get in today’s world about nappy changing? How about this one: the less it happens, the better. Pampers and Huggies make disposable nappies designed to last 12 hours without the need for a change. The idea is that parents don’t have to be interrupted in the midst of other activities with their wee ones. Babies can remain strapped into car seats and strollers and carry cots. They don’t have to risk being woken at night.

What’s another message that we get in today’s world about nappy changing? How about this one: the less it happens, the better. Pampers and Huggies make disposable nappies designed to last 12 hours without the need for a change. The idea is that parents don’t have to be interrupted in the midst of other activities with their wee ones. Babies can remain strapped into car seats and strollers and carry cots. They don’t have to risk being woken at night.

Modern society creates more and more devices that reduce babies’ opportunities to feel their parents’ touch. Of all the senses, touch is the most important for babies. It is the first sense to develop in the womb and the most developed at birth. Skin is our largest organ, and the sensations that skin sends to the brain are so powerful that they act as pain relief. In our evolutionary history, babies spent much more time experiencing touch, strapped as they were to a parent’s body during the day and sleeping next to a parent’s body at night. Modern babies experience an extremely different type of infancy than did our forebears.

Yes, babies adapt to the modern world. Skeptics will reply that babies are clearly surviving in today’s world of nappies, transport devices and sleeping arrangements. I agree, they are. But I also know that without sufficient touch and physical attention, babies die. That was one of the points to come out of studies of Romanian orphans. Infant humans depend on the physical presence of another human being in order to survive.

Could the decreasing amount of touch that modern babies receive be one of the reasons that our society is witnessing an increase in behavioural problems associated with emotional regulation? The most fundamental pathways that the brain is forming during the early years are the ones that enable to us to cope with – that is, regulate – our emotions.

So maybe it would be better if disposable nappies weren’t quite so efficient? Maybe it would be better for babies’ emotional health if nappy companies could find ways to inform parents about the crucial importance of touch and cuddling and feeling Mum’s warm fingers on your skin — even while they search for ways to keep urine from reaching a baby’s skin.

That’s one of the aims of Real Nappy Week. The celebrations aren’t designed only to highlight the value of non-disposable nappies, but to get us as a culture to rethink the whole business of nappy changing.

That’s one of the aims of Real Nappy Week. The celebrations aren’t designed only to highlight the value of non-disposable nappies, but to get us as a culture to rethink the whole business of nappy changing.

So what’s one final modern-day message to which we might pay attention? How about the way in which our fear of sexual abuse now overlaps with nappy changing?

Many nurseries now have a policy that requires two members of staff to be present when nappies are changed, in order to guard against the risk of inappropriate touch. We are scared that the people who have been vetted to take care of our children might harm them, and nakedness makes nappy changing seem a particularly vulnerable setting.

Videos that instruct new parents on how to change nappies are frequently shot from an angle that avoids revealing babies’ genitals, or are edited so that the genitals are blurred out. How ironic that the very parts of the body that generate the need for a nappy change cannot be shown on film. In our struggle to come to terms with the very real risks that children face of being sexually abused, we have further sexualised our youngest children.

In the run-up to Real Nappy Week, my team released our brief film ‘dance of the nappy’. The film is excerpted from our longer feature-length film, ‘the connected baby’, first released in 2011 with funding from the British Psychological Society. We estimate that the longer film has now been viewed by 100,000 people, but this is the first time we have released an entire segment for public viewing on YouTube.

[huge_it_videogallery id=”11″]The film shows the intricate emotional dance that goes on between a 5-week-old baby and his mother during an ordinary nappy change. The baby’s emotional responses to his mother’s movements and facial expressions are so nuanced that it would be easy to miss them. That’s why we wanted to make the film: because such moments of connection are happening for babies across the world, but it is easy for parents to overlook them because they are so subtle and fleeting. Video footage makes it possible to slow everything down and reveal what is not apparent to the naked eye.

After filming that session, I realised the baby’s genitals were in full view. The mother realised it too. She commented on it at the time, whilst we were filming. Later, during editing, she confirmed that she was comfortable with retaining the footage. But I had to ask myself: was I comfortable with it? Was it appropriate in today’s society to show a 5-week-old baby’s genitals on a movie screen? What would I say if someone challenged my decision? What if, later, when the baby is grown, he resents having had his bum shown off to the world? What if I was accused of encouraging inappropriate touch because his genitals appear briefly but undeniably?

My decision was not to change anything. I decided that real-life nappy changing means exposing and cleaning baby’s genitals. I decided that merely alluding to that, by editing out that footage, actually feeds our modern day fear that genitals are inherently sexual, even those of a 5-week-old baby. I decided that I was making a film that was trying to show how connection is possible at all points in a baby’s day, including during an activity as ‘disgusting’ as changing a pooey nappy. Because that’s exactly what the film shows – not just a Number One, but a Number Two. And the interaction between the mum and her baby is still loving and affirming. The baby gets no sense that his bodily excrement is shameful to her. After weeks of fretting, I decided I could defend such a scene to the world.

My decision was not to change anything. I decided that real-life nappy changing means exposing and cleaning baby’s genitals. I decided that merely alluding to that, by editing out that footage, actually feeds our modern day fear that genitals are inherently sexual, even those of a 5-week-old baby. I decided that I was making a film that was trying to show how connection is possible at all points in a baby’s day, including during an activity as ‘disgusting’ as changing a pooey nappy. Because that’s exactly what the film shows – not just a Number One, but a Number Two. And the interaction between the mum and her baby is still loving and affirming. The baby gets no sense that his bodily excrement is shameful to her. After weeks of fretting, I decided I could defend such a scene to the world.

This week, I was reminded about my early worries. Since our public release on YouTube last week, I have received queries from three people, expressing unease that the film shows ‘everything’. I was relieved to realise that I now welcomed such debate, rather than feared it. Those weeks I had spent agonizing had been valuable, for they enabled me to articulate the position I take in this debate.

And here is my position: Something is emotionally askew in our modern society. On the one hand, the global company Pampers can make an award-winning film that is intentionally designed to make us laugh at babies’ unease and discomfort when they poo. On the other hand, we can be made uncomfortable by a film that shows the real poo and the parts of a baby’s body that produced it. Something is awry in our reasoning.

And here is my position: Something is emotionally askew in our modern society. On the one hand, the global company Pampers can make an award-winning film that is intentionally designed to make us laugh at babies’ unease and discomfort when they poo. On the other hand, we can be made uncomfortable by a film that shows the real poo and the parts of a baby’s body that produced it. Something is awry in our reasoning.

I like the idea that a scene of something as tediously ordinary as a pooey nappy can become a radical act. A baby boy’s bum can make us reflect in new ways on our own humanity.

So, to the grown man of the future who was once that baby boy, let me offer my thanks and my apologies now. It was your bum that offered us this gift of reflection. Your mother says in the film: “One day you might really hate that I did this in front of the camera.” I hope you don’t. Because every time I show this film, I offer you a silent, grateful thanks for the trust you placed in us that day.